- Home

- Joe R. Lansdale

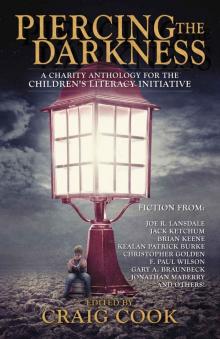

Piercing the Darkness: A Charity Horror Anthology for the Children's Literacy Initiative Page 6

Piercing the Darkness: A Charity Horror Anthology for the Children's Literacy Initiative Read online

Page 6

The cowboy’s ghost stood just inside the door, daylight streaming through him, not much more to him than if he were made of spider-webs.

“Oh” Teddy said, in a very small voice. He stared, eyes wide, mouth open. He knew he had seen the ghost before, but they were up close now, maybe ten feet apart. “Are you…what are you doing here?”

The cowboy narrowed his eyes.

“Wait,” Teddy said, realizing that he’d known all along. “You opened the closet.”

The ghost nodded at him in grim approval, the way Mr. Graham next door always did. Then he turned, gestured for Teddy to follow, and walked out of the house, passing right through the screen door.

Teddy blinked a few times. Seeing it up close like that kind of made his eyes hurt. His lips felt dry and he wetted them with his tongue, unsure what to do next. The ghost wanted him to follow, and if he understood right, had something to show him. At least that was how it seemed. He knew he shouldn’t go running off without telling ma, especially after some ghost, but she wouldn’t be waking up for at least half an hour or so. Not if today was like every other day. And if he didn’t follow, gosh he would always wonder what it was the ghost had wanted to show him.

“Damn,” he said, but only because nobody would hear.

Teddy swallowed hard, then hurriedly put the Christmas cookie tin back into the closet, grabbed the old sweater from its hook, shut the door tight, and rushed outside, careful not to let the screen door bang behind him.

««—»»

It felt like the kind of thing you ought to keep secret, partly because it seemed special and Teddy wanted it all to himself, and partly because he didn’t want anybody to think he’d lost his marbles. So as he followed the ghost around the side of his house and through the Mariottes’ backyard, Teddy tried to look like nothing at all out of the ordinary had happened today. He pulled on the ratty old sweater, realized immediately it had to have belonged to his daddy, and smiled to himself. The mothball smell didn’t bother him. The sweater hung low enough to cover the gun hanging in its holster. Combined with the sweater, it made him feel really grown up.

The ghost ambled sort of leisurely, like he wasn’t in any hurry, but Teddy knew the cowboy was hanging back to make sure he could keep up. Every couple of minutes the specter glanced over his shoulder, then sort of nodded to himself as he kept on, leading Teddy out onto Navarro Street and then onto the dirt road that led out to Hatton Ranch. When the ghost walked in sunlight and Teddy looked at him straight on, he could see right through the fella, like he was cowboy-colored glass. But whenever the gunslinger passed into the shadow of a tree or a telephone pole, he seemed more there somehow, like in the dark he might fill in entirely.

Only one car went by on the dirt road, kicking up dust that swirled right through the ghost, obscuring him from sight for a few seconds. The car—a brand spanking new Thunderbird—kept on going. The old, jowly fella behind the wheel did not so much as glance at the cowboy, but he gave Teddy a good long look as he drove by. Teddy’s face flushed all warm and the gun weighed real heavy on his hip, but the car kept on going and soon even the dust of its passing had settled again.

The cowboy had stopped up the road a piece, leaning against the split-rail fence that marked the boundaries all around the huge spread of the Hatton ranch. He waited while Teddy caught up.

“Where are we going?” Teddy asked, keeping his voice low and glancing around. If people like the porky old fella in the T-Bird couldn’t see the ghost, anyone watching him would think he was talking to himself. He didn’t want stories like that getting back to his ma.

The ghost didn’t answer, though. Instead, he nodded in an appreciative way, wearing the kind of expression Teddy remembered on his daddy’s face now and again. Then he cocked his head, indicating that Teddy should follow, and hopped the fence.

Teddy hesitated. He licked his lips. His whole body felt prickly, like his hands or arms sometimes did if he laid on them wrong. Ma would say his hand had fallen asleep, but Teddy knew it had to do with the blood inside him not flowing right ‘cause of the position he’d been in. Rachel had told him that, and it was just the sort of thing the Beddoes girls had always been smart about.

It wasn’t that he had suddenly become afraid of the ghost. Heck, that gunslinging specter had to be the coolest thing he could ever have imagined—and it had occurred to him that he might be imagining it. But trespassing on the Hatton ranch, well, that could get him in trouble. Old man Hatton had run Teddy’s daddy off his land dozens of times in the old days, at least according to Ma, and Teddy didn’t like the idea of being run off.

The cowboy turned, cocking his head like a bird. This time when he beckoned, there was a little impatience in him, and suddenly none of this seemed as much of a lark as it had a few minutes ago. Something in the cowboy’s face, what little Teddy could see of it, considering the sun passed right through it and all, told him they had serious business on the Hatton ranch.

Teddy swallowed hard, looked around to make sure no one was watching, and then threw one leg over the fence. Then he was on the other side and running like hell after that cowboy, toward a stand of trees fifty or sixty yards from the road, and a giddy ripple went through him. So what if old man Hatton ran him off? He’d run Daddy off, and Teddy liked the idea of being like his daddy. He liked that a lot.

Heck, the old guy hadn’t killed his daddy. The Koreans had done that.

“What’s your name?” he asked the cowboy, when they were on the other side of a tree-lined rise, walking across open graze land that looked more like scrub than field. No wonder there weren’t any horses around when this part of the ranch gave them nothing to nibble on.

The ghost gave him a strange look, then, half-smile and half-frown. Teddy got that look a lot in town, especially from folks in McKelvie’s store. Ma said people didn’t know what to make of Teddy, but she didn’t say it like it was a bad thing. She said it proud, like it mattered to her. She said he was smart and grown-up for his age, and folks weren’t used to little boys who could speak for themselves. One time Mrs. McKelvie overheard Ma saying something like that, and said children ought to be seen and not heard, and Ma had said that someday the whole world was gonna hear from her Teddy.

He’d beamed for the rest of that day. She’d even bought him licorice.

They didn’t get over to McKelvie’s store much lately. Most of the time, his ma said she was too tired to walk that far. Teddy would have liked some of that licorice, but he never complained. With everything Ma did for him, he knew it would be ungrateful, and Mr. Graham always told him that was one thing he ought never to be.

The cowboy didn’t talk at all. Teddy had sort of figured that out, but the questions kept coming out of him, like he had no control over his mouth at all. Finally he managed at least to turn his babbling into just plain talking. He told the ghost about all the books he’d read about gunslingers and whenever he played cowboys and Indians, he pretended he had a pair of Colts strapped to his hips. He even demonstrated his technique, drawing invisible guns and firing, making the pa-kow sound with his mouth. As soon as he heard himself, he stopped. Out there alone on the rough land of the Hatton ranch, it sounded kind of childish. And the gun—the real gun—banging against his hip seemed to get heavier.

Teddy hitched up the gun belt, and his pants, which had started to slide down from its weight.

“Are we almost wherever it is we’re going?” he asked. “We’re awful far from home and I oughta be there when Ma wakes up. Or at least home for dinner. I don’t want her to worry.”

That’s when they came to the fence. Maybe the Hatton property kept going beyond it, and maybe it didn’t. On the other side was a stretch of woods he couldn’t see the end of from here, and there were empty beer bottles scattered on the ground on either side. Some pop bottles, too, but mostly beer. Teddy looked at them, wondering who would come all this way just to drink beer. Then he thought of Artie and the goons he palled around with, and he had

a pretty good idea.

When the ghost picked up a couple of bottles, one in each hand, Teddy’s jaw dropped. Ma would’ve said he was trying to catch flies, and he did feel like a dope just standing there like that, but he couldn’t believe what he was seeing. The ghost—barely there at this angle, the sun bleaching him out like the yellow scrub grass—actually touched the bottles, picked them up and set them on the fence rail.

“How did you do that?” Teddy asked at last.

The ghost winked, but kept going, picking up more bottles and gesturing for Teddy to do the same. Between the two of them they set up more than two dozen empty beer and pop bottles, all along the rail, and by then Teddy had figured out just what they were up to out here.

Target practice.

The ghost led him a dozen paces back the way they’d come. Careful, nice and easy, not like some high noon gunfight, the cowboy took out his phantom pistol, cocked it, and pulled the trigger.

Teddy flinched, waiting for the gunshot, but it did not make a sound.

The last bottle on the left shattered, glass showering to the ground.

“Wow,” Teddy whispered.

The cowboy gestured for him to try it. Teddy’s hands shook as he took off his daddy’s old sweater and drew the old Army pistol. He had seen enough movies and read enough books to understand the basics—which end the bullets came out of and how to pull the trigger—but aiming the thing took a bit of getting used to. For a few seconds he just tried to get used to holding the gun straight, realizing that if he supported his right wrist with his left hand, he could just about keep it steady.

He pulled the trigger.

Nothing happened. The gun did not kick in his hand the way the cowboy’s had. No glass shattered. Disappointment flooded through him. All this way, standing there with a ghost, and he didn’t have any bullets.

The cowboy held out his hand. Teddy flinched, afraid the ghost would touch him. It never would have occurred to him if he hadn’t seen the cowboy pick up those bottles, but now the idea of being touched by a ghost—a dead man, though he felt sort of sad thinking of his new friend that way—gave him the shivers.

If the cowboy noticed Teddy’s reaction, he didn’t let on. Warily, Teddy handed him the gun. The moment when the ghost lifted its weight from his grasp made him catch his breath, smiling nervously.

“You’re really here,” he said.

The ghost shook his head with that same indulgent smile. Teddy missed his daddy something fierce when he saw that look, but still he was glad he had met the ghost and that they were out here having this adventure. He had already decided he would tell Sedesky about it, but not Rachel. A girl wouldn’t understand. And he bet Rachel Beddoes didn’t even believe in ghosts, but Sedesky did. Ghosts scared the crap out of Mikey Sedesky. Teddy would have to tell him there wasn’t anything to be scared of.

The ghost opened up the gun—Teddy didn’t really see how he’d done it—and slid out the cylinder where the bullets went. All of the chambers were empty. But the cowboy didn’t seem at all surprised. He just lifted the gun up to his face, pursed his lips, and blew into the empty chambers, not like he was trying to clean dust out of the cylinder, but nice and easy, like breathing.

Then he snapped the cylinder shut, gave it a spin, and handed the gun back to Teddy.

The metal felt cold, the gun heavier than before.

And this time, when Teddy pulled the trigger, the gun kicked in his hands so hard that all the bones in his arms hurt. But like the cowboy’s gun, his daddy’s old pistol fired quiet bullets.

Of course, Teddy’s shot didn’t hit much more than a few leaves in the trees beyond the fence. But the cowboy demonstrated how he ought to stand and hold the gun, and sight along the barrel, and Teddy did his best to mimic the ghost.

It took over an hour, but he managed to shoot two of the bottles right off the fence, and all the while, the gun never ran out of bullets, and never made a sound.

When Teddy looked over and saw the sun sinking low, a little tremor of panic went through him. He slid the gun into its holster and tugged the ratty sweater back on to cover it.

“Tomorrow I’ll do better,” he said as he turned to bid the ghost farewell, but the cowboy had vanished in the twilight.

Teddy was alone.

Hitching his pants up, he ran all the way home.

««—»»

That night, Teddy lay in his bed, staring at the ceiling without really seeing it. It seemed almost as if the images in his mind’s eye were projected on that blank surface, and he played out the day’s events over and over. A ghost? Thinking about it now, it amazed Teddy that he had not run away screaming, but in the moment, with the cowboy right there in front of him and so real, he had known he had nothing to fear. The gunslinger had kind eyes.

Now he couldn’t sleep. It felt like Christmas. Not the excitement of Christmas Eve, knowing that Santa would be coming within hours, but the following night, after spending an entire day opening presents and celebrating and running over to Sedesky’s so they could compare notes about what they’d gotten.

There had been no comparing notes with Sedesky tonight. He had to think about what he wanted to say about what had happened to him today. Maybe if he tried to arrange for Sedesky and Rachel to come over tomorrow, and the ghost came back, they would see him, too. If not, he knew they would never believe him. They might wish they could see a ghost themselves, but if they weren’t going to get to see one, they weren’t going to allow the possibility that Teddy had, either. Sedesky and Rachel were his friends, but fair was fair. He understood that.

Teddy yawned. His eyes burned, he was so tired. Really, it wasn’t so much that he could not have gone to sleep, as that he did not want to. No matter how excited he might be, if he just closed his eyes and turned over, he knew he would drift off eventually. But the events of the day were crystal clear in his mind—fully real. And he worried that if he slept, when he woke in the morning the hours he spent with the ghost would have blurred some, and started to seem like maybe they were a dream. He hated that idea. Teddy wanted to hang onto the certainty of the memory as long as he could.

Yet amidst the nearly giddy aftermath of his day, something else lingered, niggling at the back of his mind, and that gave him another reason to stay awake. If he drifted off to sleep, he knew his thoughts would turn in that direction, and he did not like the troubling things that waited there.

After target practice at the Hatton ranch, Teddy had rushed home as fast as his legs could carry him. Twice he’d had to halt and drag up the gun belt before its weight pulled his pants down to his knees. In the gathering dusk he had raced along Navarro Street as lights came on inside some of the houses, families sitting down to dinner. He had cut through the Mariottes’ backyard and into his own. Breathing hard, more than a little frantic at the idea of going in through his front door wearing his daddy’s old ratty sweater and carrying his gun, Teddy had looked around for a hiding spot. He’d pulled off the sweater and wrapped up the gun and belt, then tucked the whole package behind the coiled up garden hose before rushing inside.

He needn’t have worried. Ma had still been asleep. It had been a simple thing to retrieve the gun and return it to its rightful place, and all the while she hadn’t stirred. It worried him.

The radio voices still filled the house, and there his ma lay, curled up on the sofa, snoring lightly. The last of the day’s light filled the room with a blue gloom, and after he’d put the gun away, Teddy went and clicked on the floor lamp by the sofa. He knelt beside his ma and shook her gently awake.

“Ma, you’re still sleeping,” he told her, and the words sounded so dumb to him. “Sorry I’m so late. I was out with Mikey and we kinda lost track of time.”

Such a weak excuse, and he hated to lie to her. It made him feel ashamed. But Ma had smiled sleepily and then, as she sat up and saw the darkening windows and realized the time, she had frowned deeply.

“Look at the time,” she said. “You must

be starving, and I haven’t fixed anything for dinner.”

“How about breakfast for dinner?” Teddy had suggested.

Sometimes, as a special treat or when they were in a hurry, his ma would make bacon and eggs for dinner. They always made a big deal out of it, like they were getting away with breaking the rules somehow.

Tonight, it had not seemed so special. His ma had barely touched her eggs and only had a couple of pieces of bacon. Teddy had been famished, but the weight of guilt slowed him down and when the eggs got cold he stopped eating. His ma had asked him to clean up the dishes, apologized, and then gone back to the couch, and when Teddy asked if she was okay, all she would say was that she was a little under the weather.

“I’ll be right as rain, tomorrow,” she had promised.

By the time Teddy finished up with the dishes, she had fallen asleep again. He had left her with her radio voices and gone out back to retrieve the sweater and the gun belt, quickly returning everything to the painted-over closet in the front hall.

Now, lying in bed, he could still feel the weight of the gun tingling in his hands, and he could still hear the low murmur of radio voices drifting up to him from below. His ma had slept on the sofa before, but she had never been asleep when it was time for Teddy to go to bed, not even when she had the flu. Tonight he had brushed his teeth and put on his pajamas and gone down to say good night, but he had not wanted to wake her, so he had kissed her softly on the cheek and gone upstairs.

He didn’t like sleeping upstairs all by himself, but if his ma had the flu again, he wanted her to get the rest she needed. She had promised she’d be right as rain come morning, and he hoped she was right. But deep down he doubted that, and it made him wonder if she doubted it, too.

««—»»

Teddy opened his eyes slowly, only vaguely aware of the hiss of static from downstairs. The radio station had gone off the air for the night. As that bit of information formed in his mind, he realized with no little surprise that he had fallen asleep after all. Quickly he remembered the ghost, and almost as quickly he wanted to see the cowboy again. As he had feared, already the image had lost its sharpness in his mind, and he could not summon a complete picture of how the ghost had looked when he had first seen it, out on the street in front of his house.

More Better Deals

More Better Deals The Elephant of Surprise

The Elephant of Surprise Piercing the Darkness: A Charity Horror Anthology for the Children's Literacy Initiative

Piercing the Darkness: A Charity Horror Anthology for the Children's Literacy Initiative Bullets and Fire

Bullets and Fire Freezer Burn

Freezer Burn The Two-Bear Mambo

The Two-Bear Mambo The Big Book of Hap and Leonard

The Big Book of Hap and Leonard Briar Patch Boogie: A Hap and Leonard Novelette

Briar Patch Boogie: A Hap and Leonard Novelette A Bone Dead Sadness

A Bone Dead Sadness Steampunked

Steampunked Dead in the West

Dead in the West The Ape Man's Brother

The Ape Man's Brother The Bottoms

The Bottoms Cold in July

Cold in July The Complete Drive-In

The Complete Drive-In Bumper Crop

Bumper Crop Deadman's Road

Deadman's Road Captains Outrageous

Captains Outrageous Hap and Leonard: Blood and Lemonade

Hap and Leonard: Blood and Lemonade Hap and Leonard Ride Again

Hap and Leonard Ride Again Magic Wagon

Magic Wagon Coco Butternut

Coco Butternut Jackrabbit Smile (Hap and Leonard)

Jackrabbit Smile (Hap and Leonard) Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man's Back

Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man's Back Leather Maiden

Leather Maiden Cold Cotton: A Hap and Leonard Novella (Hap and Leonard Series)

Cold Cotton: A Hap and Leonard Novella (Hap and Leonard Series) All the Earth, Thrown to the Sky

All the Earth, Thrown to the Sky Dead Aim

Dead Aim Edge of Dark Water

Edge of Dark Water Devil Red

Devil Red The Thicket

The Thicket Flaming Zeppelins

Flaming Zeppelins Rusty Puppy

Rusty Puppy Hyenas

Hyenas Black Hat Jack

Black Hat Jack Rare Lansdale

Rare Lansdale Christmas With the Dead

Christmas With the Dead The Best of Joe R. Lansdale

The Best of Joe R. Lansdale A Fine Dark Line

A Fine Dark Line Rumble Tumble

Rumble Tumble Waltz of Shadows

Waltz of Shadows The Magic Wagon

The Magic Wagon Stories (2011)

Stories (2011) By Bizarre Hands

By Bizarre Hands Act of Love (2011)

Act of Love (2011) Honky Tonk Samurai (Hap and Leonard)

Honky Tonk Samurai (Hap and Leonard) Hap and Leonard

Hap and Leonard A Pair of Aces

A Pair of Aces Vanilla Ride

Vanilla Ride Bad Chili

Bad Chili The Killer's Game

The Killer's Game Paradise Sky

Paradise Sky House of Fear

House of Fear Lost Echoes

Lost Echoes Fender Lizards

Fender Lizards Blood Dance

Blood Dance Hot in December

Hot in December Bubba and the Cosmic Blood-Suckers

Bubba and the Cosmic Blood-Suckers Savage Season

Savage Season The Boar

The Boar Miracles Ain't What They Used to Be

Miracles Ain't What They Used to Be Deadman's Crossing

Deadman's Crossing Bad Chili cap-4

Bad Chili cap-4 Hoodoo Harry

Hoodoo Harry Incident On and Off a Mountain Road

Incident On and Off a Mountain Road High Cotton: Selected Stories of Joe R. Lansdale

High Cotton: Selected Stories of Joe R. Lansdale Devil Red cap-8

Devil Red cap-8 Jackrabbit Smile

Jackrabbit Smile Savage Season cap-1

Savage Season cap-1 Sunset and Sawdust

Sunset and Sawdust Hyenas cap-10

Hyenas cap-10 Captains Outrageous cap-6

Captains Outrageous cap-6 The Steel Valentine

The Steel Valentine Mucho Mojo

Mucho Mojo Vanilla Ride cap-7

Vanilla Ride cap-7 Mucho Mojo cap-2

Mucho Mojo cap-2 The Two-Bear Mambo cap-3

The Two-Bear Mambo cap-3